Engelmann oak (Quercus engelmannii) is best known by superlatives, such as “the rarest tree-oak species in the United States” or “the most sensitive type of oak woodland in California.” Today, Engelmann oaks are found primarily in rare, scattered groves and are restricted to Southern California and northern Baja California west of the desert region. The species’ biogeography is unique among California oaks, as it is a subtropical white oak in a Mediterranean climate. Taxonomists consider Engelmann oak to be the northwestern-most member of a group of Mexican white oaks (including Quercus oblongifolia, Q. arizonica, Q. grisea). These sister species primarily occur in the Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range in north-central Mexico and are separated from the Engelmann oak by hundreds of miles of desert regions.

Lowland populations of Engelmann oak have suffered from post-World War II expansion of suburban communities in southern California. In addition to the direct conversion of oak woodlands to housing, other human activities (e.g. fire and over-use by livestock) have altered the ecology of some Engelmann oak woodlands, apparently resulting in reduced survival and recruitment. Despite these sensitivities, Engelmann oak appears to have expanded its distribution (or at minimum recovered distribution lost) since 1928.

Why should there be a trend towards more Engelmann oaks? The answer lies in aerial photographs taken in 1928 and 1929. In San Diego County, these photographs were taken to collect information for the first US Geological Survey topographic maps, and to establish land and tax status. In most cases, they show that the landscapes of the late 1800s and early 1900s were heavily altered by overuse and inappropriate farming practices. But since that time, the weather and better land management practices have provided better conditions for oak regeneration. All of the methods we have used to establish trend (examination of tree rings and sequential aerial photography) indicate that today there are more Engelmann oaks and larger, more vigorous trees than when the photographs were taken in the late 1920s.

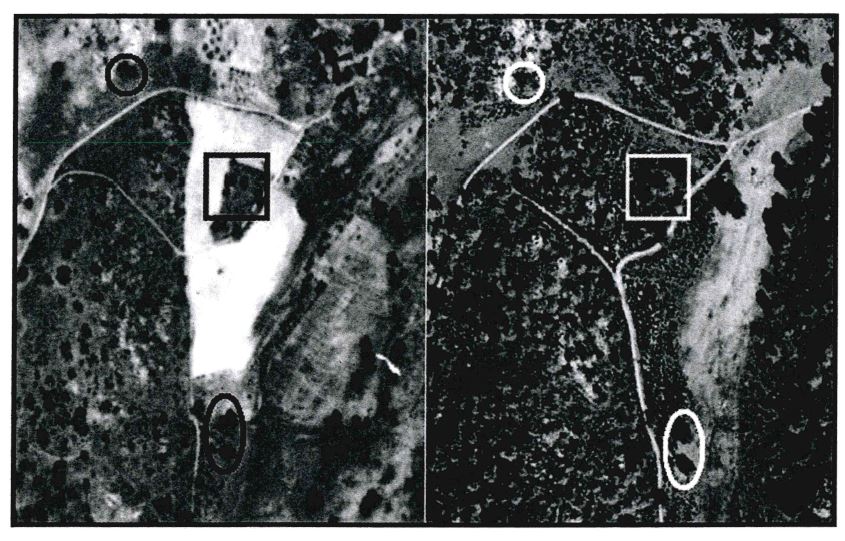

FIGURE 1: Recovery of Oak Woodlands in the Foothills of San Diego County. These two photographs, taken in 1928 and 1990 show the growth of Engelmann oaks (Quercus engelmannii) and coast live oaks (Q. agrifolia) on rangelands east of the town of Ramona. Reference points are marked with circles and a square to show change over the 6 decades. In 1928, it appears that the area has been used for dry farming or pasture, surrounded by heavily damaged woodlands; in 1990, the outline of the tilled area has disappeared into sage scrub, grassland, and woodland. Note the recruitment of Engelmann oaks on the previously disturbed slopes, as well as the buckwheat/sage scrub vegetation on the area previously used as farmland.

But saying we have more trees is perhaps too great a simplification; not all stands of Engelmann oaks are doing better now than they were in the 1920s. There are places where overuse continues to shift biomass of stands into larger older trees, rather than a broader range of size and age classes. Further, there are stands where larger trees are dying as rapidly as smaller trees, perhaps in association with frequent fires. These stands rapidly decline in density and distribution. While oak stands have a remarkable ability to withstand decades of abuse, they eventually give way to grasslands if improperly managed. The good news is that the examples of poor management are uncommon; over 75% of the stands studied were increasing in number and size of Engelmann oaks.

Tom Scott

prepared and edited by Adina Merenlender and Emily Heaton