Oaks ‘n’ Folks – Volume 18, Issue 1 – February 2002

Effects of Rural Residential Development on the Breeding Birds of Placer County’s Foothill Oak Woodlands

Placer County, which spans from the Central Valley to the crest of the Sierra Nevada, has the fastest growing human population in California, with a growth rate of 3.5% in 2000. Much of this population growth is occurring in the county’s foothill oak woodlands, 93% of which are privately owned and over 50% of which (30,000+ acres) have rural residential or urban land-use designations in the County General Plan. Concern about this rapid growth and the loss of open space and rural character led to the development of the Placer Legacy Open Space and Agricultural Conservation Program, a program of the County of Placer that seeks to balance growth with the conservation of open space and wildlife resources. Because foothill oak woodlands are rapidly urbanizing and poorly protected, while at the same time treasured for their scenic and wildlife values, much of the program’s early emphasis has focused on preserving large areas of oak woodland. In addition, the Placer Legacy Program aims to help rural residential landowners manage their properties to preserve wildlife, sensitive resources, and water quality.

In 2000, with the support of the Placer Legacy Program, we initiated a bird-oriented study to assess the effects of rural residential development on oak woodland habitat. Birds are recognized as excellent indicators of ecosystem health, are relatively easy to assess, and are the focus of a new statewide Oak Woodland Bird Conservation Plan by California Partners in Flight. The basic habitat requirements of most oak woodland birds are reasonably well-understood, such that we can anticipate the direct effects of replacing oak trees with high-density housing developments and shopping malls. In the Placer County foothills, however, much new development is low- to mid-density (1-20 acre parcels); tends to retain some oak trees; and lies within a patchwork landscape of small farms, rangeland, horse pastures, and ranchettes. The indirect effects of this less intensive type of development are poorly understood. Previous studies suggest that for some bird species, the amount and configuration of suitable habitat (oak woodlands in this case) in the surrounding landscape may be nearly as important as the immediate habitat conditions. We asked the question: Are there certain species that are sensitive to development density, the surrounding landscape, or both? Such knowledge may be particularly valuable when candidates for open space preservation contain trees of similar age and size (as they do in foothill oak woodlands of Placer County), since alternative criteria will be needed to rank/prioritize the candidates.

To answer our question, we selected a semi-random set of 75 points within oak woodlands representing a range of different development densities in Placer County’s foothill belt (Figure 1). We visited each point twice during the Spring of 2000 and carefully counted the number of each bird species seen and heard during a 6-minute period. We then used Geographic Information Systems (GIS) computerized maps of parcel size, development status, and vegetation to calculate the development density, amount of oak woodland habitat, and habitat diversity in the landscape surrounding each point (up to 4 km). Using statistical models, we analyzed the association between these landscape factors and the number of individuals detected at a point (abundance), species by species.

Model Results

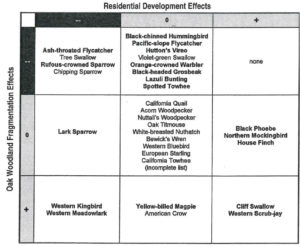

Of the 48 breeding species common enough to analyze statistically, 24 exhibited associations between landscape factors and abundance (See Table 1). Species that appeared to be negatively affected by development density included the lark sparrow, rufous-crowned sparrow, and western meadowlark; while the black phoebe, house finch, and western scrub-jay were positively associated with development.

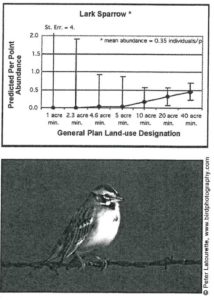

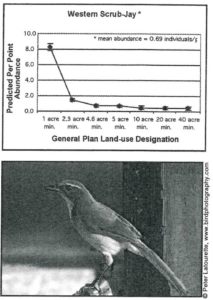

For two of the more development-sensitive species, we used our models to predict bird numbers under a range of development density scenarios corresponding to existing Placer County General Plan designations. Our models predict that lark sparrows would be virtually non-existent at a 1-acre-per-parcel density. Furthermore, predicted abundance does not level off as parcel size increases (See Figure 2), suggesting that even moderate-density development has a negative impact on lark sparrow abundance. The abundance of western scrub-jays, which may negatively impact other birds as a predator of eggs and young, was predicted to be more than ten times higher at a 1-acre-per-parcel density than at a 40-acre-per-parcel density.

These results suggest that residential development in the oak woodland landscape may indirectly affect a few bird species outside the area of immediate impact. Potential causes for declines include urban-associated predators (e.g., domestic cats, raccoons, and rats), habitat degradation (e.g. mowing and intensive grazing), urban edge avoidance, and problems with dispersal.

Several other species, including the orange-crowned warbler and Hutton’s vireo, were not development-sensitive but were shown to increase with the amount of oak woodland and/or habitat diversity found in the surrounding landscape. This suggests that development that retains oak woodlands (including a significant interior live oak component within the blue oak matrix) may still provide adequate habitat for these species. Many oak woodland-dependent species, including the western bluebird and acorn woodpecker, did not show evidence of landscape sensitivity but are known to depend on specific habitat elements like old or dead trees with natural cavities for nesting.

Implications for Conservation Planning

Although additional years of data collection are needed to validate our models over time, our preliminary results highlight the fact that the importance of development density and surrounding landscape may vary greatly by species. Conserving habitat for birds across this spectrum is no easy task, and may hinge upon several complementary strategies.

- Preserving the remaining large, undeveloped parcels of oak woodland (>40 acres) should help ensure the local persistence of landscape-sensitive species.

- In order to maintain development-sensitive species in the rural residential landscape, new development should be concentrated into relatively small areas, and subdivision of rural residential parcels into small ranchettes (1-5 acres) should be limited.

- Managing oak woodland on small parcels to retain a variety of habitat components—including large trees, snags, and interior live oaks—can provide habitat for a host of human-tolerant bird species.

- Oak woodland bird species have varying habitat needs, so maintaining a mosaic of habitat types is important for preserving a suite of oak woodland species.

See the California Partners in Flight (CPIF) Oak Woodland Bird Conservation Plan (draft available at http://www.prbo.org/calpif/htmldocs/oaks.html) for more information on this topic.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Placer County Planning Department, the David and Lucille Packard Foundation, and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation. In addition, this study would not have been possible without the generous cooperation of close to 50 different Placer County landowners who allowed access to their property.

prepared and edited by Adina Merenlender and Emily Heaton

Diana Stralberg, Point Reyes Bird Observatory

Brian Williams, Williams Wildland Consulting, Inc.