Oaks ‘n Folks – Volume 18, Issue 12 – July, 2002

Most people are unaware that there are many more species of bees than just honeybees and bumblebees. In fact, there are at least 20,000 species of bees in the world, with at least 3,500 different species in North America. Bees range from the size of a tiny fly to a large carpenter bee and can come in many colors, from black to red to bright metallic blues and greens (like the Agapostemon pictured below). Between 60-70% of the world’s vascular plants rely on insects for pollination. Bees are important for pollination of both wildland plants and agricultural species. In North America alone, estimates of the value of bees (native bees and the introduced honey bee) as pollinators of crops ranged between $4.6 billion and $18.8 billion in the late 1980’s.

Bees and Oak Woodlands

Oak woodlands, when relatively intact, contain a diverse flora interacting with a diverse pollinator fauna (Dodson 1993). In recent times, oak woodlands have experienced profound changes that have led to significant fragmentation of these habitats. These changes involve various combinations of grazing, conversion to agriculture, altered fire regimes, and fragmentation due to development. Although our understanding of the effects of fragmentation on vertebrate species in oak woodlands is increasing, we know very little about the effect of these changes on invertebrate communities. In particular, we know virtually nothing about how changes in habitat size and isolation affect the flora and the abundance and diversity of pollinators of oak woodlands.

Napa and Sonoma counties once had extensive oak woodlands. Both historic and recent land use practices have contributed to a dramatic loss and fragmentation of these oak woodlands. In the Napa Valley, virtually no un-fragmented bottom lands remain. In recent years, intensification of agricultural land use, particularly new vineyard development, has posed a significant threat to oak woodlands in the North Coast. In some areas, conversion of woodlands to vineyard has been extensive. This rapid fragmentation affects surrounding plant and animal communities directly through habitat loss and indirectly through effects associated with edges (e.g. increased disturbance, invasion by exotics) and isolation.

Given that fragmentation is happening, the challenging scientific question is how to minimize the impact of these changes on the natural community. To do this, we need a baseline data set to compare changes in diversity; an understanding of the effects of fragmentation; and experimental evaluation of techniques for minimizing the impact of fragmentation.

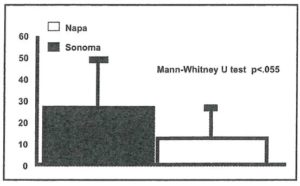

Along with a number of collaborators, I am studying the importance of the remaining oak woodlands for the long term survivorship of bees and the plants that they pollinate, as well as ways to increase the ecological function of vineyards. Our preliminary work showed a difference in the number of bees found in the two counties (Figure 1). This suggested to us that the importance of individual oak woodland patches for supporting bee diversity may depend on the configuration of the surrounding landscape, particularly on the amount and spatial distribution of nearby vineyard and oak woodland habitat.

To study the effect of surrounding habitat, we are working with several vineyards in Napa and Sonoma (Chateau St. Jean, Kunde, Mondavi, Stag’s Leap, Quintessa, Hudson and Saintsbury) to document the pattern of bee diversity and to identify the critical host plant and habitat characteristics for the bee fauna. To separate the influence of geography from that due to the amount of vineyard in the surrounding landscape, we have characterized the degree of “vineyardization” for all of Napa and Sonoma counties using a Geographic Information System (GIS). We are studying bees in areas heavily influenced by vineyards versus areas lightly influenced by vineyards (as defined by the GIS analysis). To date, we have found over 30 genera and over 100 species, including two new species of Andrena. These data will provide a critical baseline of data for years to come.

Bees and Vineyards

Cover crops have substantial effects on several components of vineyard ecosystems. They can enhance the natural control of arthropod pests, suppress weeds, and increase nitrogen. Although most studies of the effects of cover crops have focused on the impact on agricultural pest insects (Ingels et al. 1994, Bugg et al. 1996), anecdotal evidence suggests that cover crops may provide important resources for native bees (R. L. Bugg pers. comm.). In landscapes with extensive conversion to vineyards, vineyards with cover crops may provide critical corridors between the remaining fragments of natural oak woodlands. This suggests that using native plants in the matrix of cover crops may be an important tool for restoration and maintenance of biodiversity in these habitats.

We are working with the Sonoma Valley Vintners and Growers Alliance and the Southern Sonoma County Resource Conservation District to develop cover crops that will improve the ecological function of vineyards. Using the data that we have collected on host plant use by solitary bees, we have identified species to use as cover crops. We are testing how these species impact both vineyard and grape quality, as well as habitat quality for several taxonomic groups, including birds and bees. We are hoping to achieve a win for both wine and wildlife.

The loss of oak woodland in California is an issue from San Diego County to the Oregon border. The region that includes Napa, Sonoma, Lake, and Mendocino counties represents the continuum from almost complete loss of bottomlands in the Napa Valley to the relatively pristine Angelo-Northern California Coast Range Preserve administered by UC-Berkeley. Napa and Sonoma are areas where we can examine the effects of fragmentation both early and late in the process. Data collected from these more heavily impacted regions are an important resource for areas just beginning to experience development. Research in these modified landscapes helps us understand the critical patterns of diversity and the ecological processes that maintain the integrity of these ecosystems. Understanding the effects of fragmentation on plant-pollinator relationships has implications for management of wildlands and agricultural lands. The data we are collecting will provide a starting point for evaluating land use and for targeting areas of special concern in those regions that have not yet experienced high levels of fragmentation. This data will also aid in developing strategies for minimizing impacts in regions undergoing development.

Bugg, R. L., G. McCourtey, M. Sarrantonio, W. T. Lanini, and R. Bartolucci. 1996. Comparison of 32 cover crops in an organic vineyard on the north coast of California. Biological Agriculture and Horticulture. 13:65-83.

Dobson, H.E.M. 1993. Bee fauna associated with shrubs in two California chaparral communities. Pan- Pacific Entomologist 69(1) 77-94.

Ingels, C., M. V. Horn, R. L. Bugg, and P. R. Miller. 1994. Selecting the right cover crop gives multiple benefits. California Agriculture 48: 43-48.

prepared and edited by Adina Merenlender and Emily Heaton. Oaks ‘n Folks – Volume 18, Issue 12 – July, 2002