Oaks ‘n Folks – Volume 18, Issue 12 – July, 2002

In California, increased residential development has resulted in conversion of oak woodlands to houses, roads, and recreational areas. The majority of oak woodlands in California’s North Coast are privately owned, making them vulnerable to this type of development. Given the continuing demand for housing development, information on how native species may be impacted is critical for conservation planning. This study was developed to increase our understanding of the complex matrix of private lands—in particular the intensity of residential development and how wildlife responds.

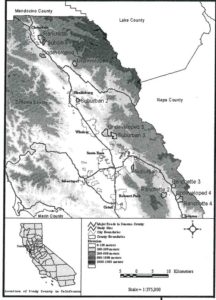

The research for this study was conducted in Sonoma County, located in northwestern California. This is one of the fastest growing counties in California, with an estimated 29% of its population living in low-density housing (1 unit on 2 acres or more). About a third of the County consists of hardwood forest and woodlands; therefore integration of oak woodland conservation with private land management is imperative.

Here we describe the effects of parcel size on bird species presence and abundance. Bird communities were selected because they are well studied, expertise was readily available, and bird habitat requirements span a wide range of landscape scales. For five years (1997-2001), birds were sampled during the breeding season at 12 mixed oak woodland sites (Figure 1) with different development densities: four undeveloped (parcels > 300 acres), four ranchette (10- to 40-acre lots), and four suburban (0.5- to 2.5-acre lots). Point counts were conducted at eight different locations at each site. These sites were located in the foothills of the Mayacmas Mountains (5-15 degrees slope and 100-200 m in elevation) and comprised a mixture of dense hardwood forests and more open oak woodlands.

FINDINGS

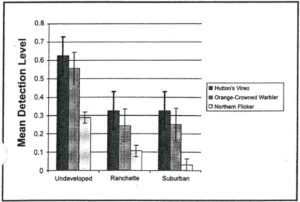

Seventy-one bird species were used in the final analysis. Examination of the entire community revealed that both development density and differences between each individual site were associated with bird community composition. Apparently, not all species are equally influenced by residential development. Figure 2 shows that Northern Flickers, Orange-crowned Warblers, and Hutton’s Vireos were detected significantly more often at undeveloped sites as compared to the more densely populated ranchettes and suburbs (using nested analysis of variance). This suggests that these species may be negatively impacted by future fragmentation from housing development. Other species were significantly more common in suburban neighborhoods such as the House Finch, Western Scrub-Jay, California Towhee, Northern Mockingbird, American Crow, and Turkey Vulture.

Results from this study indicate that the size of private property lots influences bird species composition in a mixed rural-suburban landscape. It appears that increased housing densities and associated activities in oak woodlands negatively impacted some species, while other species benefited. A variety of processes such as habitat degradation, fragmentation, predation by feral animals, competition with exotic species, and others could be influencing bird populations. Therefore conserving continuous undeveloped habitat may be important for maintaining local populations of some species. Economic incentive programs and county planning initiatives that minimize property subdivision are ways for Californians to maintain the ecological integrity of privately owned oak woodland vegetation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research would not have been possible without the wonderful landowners who have repeatedly granted us access to their property—Thank you! We would also like to thank Dan Nelson, Chuck Vaughn, Robert Keiffer, and Emily Heaton for their help with bird identification in the field and discussions of local bird natural history, and Colin Brooks for site selection assistance.

Merenlender, Adina, Kerry Heise, and Sarah Reed.

prepared and edited by Adina Merenlender and Emily Heaton